Fragments of “Performance and Beyond” appeared earlier in “The Intricate Puzzle of Performance Afterlife: Untangling the Preservation of an Ephemeral Art Form”

— Jacoba Bruneel, unpublished master’s thesis, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium, 2011.

For this publication the interview was reworked and translated by Danny Devos and Jacoba Bruneel.

Performance implies timelessness; however, gradually we detect a re-embodiment of the history of performance by means of re-enactments and other attempts at conservation. How do you position yourself, as an artist, towards the conservation of performance?

To me, performance is primarily very time and space bound, in the sense that it happens then and there, and not anywhere else. So, that is actually very important. As an artist I am not at all occupied with what happens to the performance after its occurrence. Not to organise the documentation or registration myself is in itself a conscious choice. On the contrary almost, I do not want that professional photographers attend my performances or that people take flash photographs. I do not want anybody to stand in-between the spectator and myself.

But you do have a relatively extensive archive of your performances on your website at www.performan.org (1).

That is true, but you will see that I usually have only one or a few photographs of each performance, made by rather casual spectators. The website performan.org is my CV, I did that performance and there is an image thereof, but the image is in most cases not an artwork in itself. I do not consider those images to be artworks.

They’re purely documentary?

Yes. Sometimes it is an aid for people to make a better representation of how the performance took place.

Do you feel it is important there is a kind of archivisation, that there is a genuine body of work of performance art?

Yes. I do not consider performance to be a different form of art than painting or sculpting, there is only the difference that you can no longer see the real artwork. But apart from that I feel that all these things have to be considered as artworks in and of themselves, just as land art, conceptual art, body art and even installations or video art. In my case, I just say I have made those works and I describe what the work was. It is just a description of the work in word and image, nothing more. I do not necessarily want a different approach of the artwork in the case of performance than with other visual art.

Do you see a different approach of performance nowadays than earlier?

No, as far as I am concerned, there is no difference.

And does the outside world? Because you say, you do not want another approach?

Of course I cannot speak for other artists, but I do think that in art criticism in general and in art journalism and coverage, performance is always treated as something special. I have also had exasperating discussions with people who study performance, so-called specialists. Too often they come up with special arguments when dealing with performance. They push the performance artist in more of an underdog position, saying “Well, he is a bit weird because he does not want to sell pictures of his works”. But that does not mean I do not value my artworks, I do value them, I just don’t feel, personally, that I have to take pictures of my performances and sell them. That is not my kind of thing. I do want to do something different with them. Next year, I will open an exhibition, the first time I return to a gallery in ten years (2), and I am currently researching if I can do something new with the images of my work, something different. Not just printing them on a large canvas and selling three copies of them, that is bullshit in my opinion. I feel the same way about sculptors who exhibit and sell sketches or work-in-progress drawings of their sculptures or installations. I feel that is bullshit as well. I’m kind of a fundamentalist in that respect.

How do you feel about re-enactments?

I think they are very interesting, because they are done by people who can properly value performances. I compare them to contemporary musicians performing pieces by Mozart or Bach. They perform them in their own way and bring something of themselves to the pieces. It’s about, when today you listen to musicians playing Mozart or Bach, you also pay attention to the interpretation of the work. Because you do not really know the original, you do not know how it should be, or how it really was, but in such a re-enactment or performance of classical music, you also listen to and appreciate the moment in which the interpreter plays the music. Think about how Glenn Gould interpreted and performed Bach’s music. Re-enactments are also not intended to commercialise the original performance as a kind of theatre piece. A re-enactment also only happens once, so you have a comparable situation. If the re-enacting performer would turn the work into a kind of theatrical piece, I would probably have reservations about the whole thing. But in general, I believe it is a good thing, because the reperformance of classical music is a widely accepted practice of which everyone in the music scene can see the value and use. In essence, re-enactments of performance art are the same thing, but translated to another medium. I am honoured that it is being done with work of mine while I am still alive, for Bach can no longer be honoured or impressed by what Glenn Gould did with his music. So, I feel it is a really good thing and I am very happy it is happening.

But you do feel it is very important it includes an interpretation of the work?

There’s always an interpretation because you can never know exactly how you should execute a performance or even the individual actions within the context of a performance. I have spoken to Mikes Poppe about this. Mikes is one of the first artists who re-enacted a performance of mine (3). Back then, he didn’t come to me to ask how he had to do this or that. In the case of re-enactments, artists just start from the information that is available to the public in general, because, usually, that is all the information there is. I did ask Mikes how it was to re-enact my work and it was just the same as it was for me, I recognised what he felt perfectly. Recently, he did a performance at the Academy (4) where he hit his head against a plaster sculpture and I could tell him afterwards “Tonight you’ll look like this, tomorrow like this and then you’ll feel that”. It is rather exceptional that you can be there, that you – as subject or source of inspiration – can experience that.

Do you feel it is a way in which performances can live on?

I do not know if it is the best way for performance to live on, but it is probably the best by far. But I am also very happy with the way I do it on my website: an image and a sentence. I think that’s very good as well, as merely a document.

Do you think it is important that things are done with the body of work of performance art, that it is more than just a kind of dusty archive in which facts are stored?

Yes, but it is always like that. People who have seen one of my performances, and I know this from experience, carry it with them for a long time and they also tell others about it. I think that is a very good way for performances to live on, that way it is kind of like medieval sagas and legends that are told on and on and eventually start to change. I have heard people describe performances of me that I have never ever performed. I think that’s really nice, that it is something that kind of hangs in the air and that more people are attracted by it than I expected. It is very strange to hear things come back to you on different levels as a kind of echo, with plenty of reverberations. I also hear from people who are deeply impressed, who feel extreme things during the performance. Nevertheless, it only happens sporadically that someone tells me directly about this. So, it can be very intense… It does not influence my other work, but it is a sort of recognition because it is much more difficult to express your appreciation of performance art. You do not have the same feeling or atmosphere as with the opening of an exhibition, most people do not really dare to say something to me anyway. So I do not know how they feel about it. At an exhibition opening you usually have something to drink and it is more of a social happening, but with a performance, or at least with my kind of performances, it is not that kind of event. I do not want to perform at openings anyhow, I do not want to be an attraction.

Even with our band Club Moral we do not do that kind of thing. We want people to be there for our concert and not for anything else. The audience should know why they are there and it should not be like “Oh, how nice, a gig”. That’s annoying for us and for the people who want to see the show as well.nAnd that is even more important in the case of a performance.

Is the presence of an audience crucial to your performances?

No, I have done many things without anyone present. Those are of course other kinds of works, more icon-like pieces. For example, the performance in which I lay down naked on murder sites. (5) No-one was present there. I would not have been able to do that with people present. That is also a performance, but a very different one from, for instance, the last performances I did in which I performed a series of abstract actions, one after another, that are very visual, for which I also made a soundtrack, but which is not necessarily synchronised with the actions. There everything is important and so is the presence of the audience. Not as much the number of people present, but the fact that different people are standing next to each other that all experience what is happening. I also believe the social interaction of the spectators during the performance is crucial. When a number of people are together in a space, in a certain context, and there is someone who does something and that person falls or hurts himself or that person is naked, it creates a certain tension between the spectators. That is an important aspect of what my work is about and of where I want to go to as an artist. I will not define what it is, but it is a kind of ingredient I do not control and which is of great importance.

When creating a performance, do you know whether or not there will be an audience?

Yes, the performances that do not include an audience are more impulsive because they are a kind of icon-like items of which saying I did it suffices, as a matter of speaking. Then there are other works of mine with which it does not matter whether there’s an audience, but it also collides sometimes. With some performances I cannot even tell if there is an audience or not. Then, it’s the concept that matters, with an audience, but not the number of people. Usually I prefer less people, rather than more.

Now re-enactments are made of your performances, for instance by Mikes Poppe, do you take note of the fact that the documentation you collect on your website might serve as a reference for a re-enactment?

I never take note of a possible registration when working on a performance. Whether I do something impulsively or whether I know three months in advance I will be doing a performance somewhere, that day, there, it does not make a difference to me. Actually, I do not take anything into account, and, usually, I prefer not knowing too far in advance that I have to do a performance, because it is difficult for me to say what I will be doing beforehand. In general, everything starts bubbling the moment I make an appointment for a performance, or even when there is the mere possibility of doing a performance somewhere. You might call it a kind of ‘trigger point’ that sets off a process. Then, things keep on going round in my head, unceasingly. I always have a number of things fluttering around in my head that I might or might not use at that moment. Thereafter come the practical things, how will I translate what is inside my head, how will I solve it, what do I need to do that. Usually I only start with this aspect a week before the performance, thinking about what I need concretely: attributes, time, lighting, the exact actions. Usually I know what I need, but it is not always easy to find everything, and then I am dependent on what I can find and what not. That is how it tends to work.

Often, I am only sure how everything will work the day before. This does not mean I will produce a kind of scenario, at that moment everything is in my head, I never write anything down. I do not make sketches, nothing on paper, I only have the actions, the movements. Everything is inside my head. I never try anything out beforehand either. It is that moment in which it has to happen, that is the only way, I know this from experience, the only way in which it might work. One time, I tried out something before the actual performance, and it did not work. But I had made an agreement with myself, you cannot go back and when you are lying there, it works after all. It was the performance with the rope (6), and in advance I had thought about which rope I would be using. Something that looks good and that I might swallow. I thought, yes, I will try it out before deciding, and it didn’t work. Your body, your throat, your oesophagus, it reacts, instinctively. It says swallowing a rope is not the intent and sends it back. But when you are lying there, you are lying there for one thing and one thing only, swallowing that rope, there is no other way, I did not have a choice. That is the only time I attempted something before the performance, and the… Well, you see, it is not a good idea.

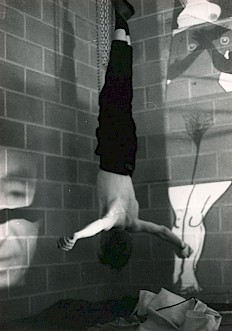

When I create a performance in which I want to hang upside down, I try it out in the sense that I check whether the system I want to use isn’t something that will cut off my feet, but those are purely technical details. I once did a performance in Brussels, with paper bags filled with paint (7), and I tried that out to see whether those bags wouldn’t rip immediately or start leaking. But physical things, no, you have to be confident in those. And that’s what performance is about as well. You do it or you don’t. And if you do it, you have to choose for what you’ve decided to do. And if it doesn’t work, just as well. I used to do a lot of things just to see if it would work, to see how far I could go. I do no longer need to do such things, I know now how far I can go. So I don’t have to experiment anymore. Just to say one thing, I know I can hang upside down for an hour; I know how to cut my own skin without bleeding out. Those are things I no longer have to do to try, that phase has passed completely. But I do have a kind of armamentarium handy that I can use, I can choose things from it and bring them together. That is why I call those last performances I did in Brussels, Singapore and Hasselt a kind of abstract expressionism, because they are abstract actions that follow each other in a certain order.

During which a recognisable sound – I use pop music and other sounds and weird things as well – forms a kind of soundtrack. The order of everything is not strictly decided in advance, the actions follow each other intuitively, as the moment prescribes and not differently. All those things coming together, they create a kind a collage or mash-up that in turn creates a kind of atmosphere people at that moment in that place are looking at together. Everything is one static but extended and yet moving moment. As an abstract painting displays an array of planes and colours, that is how my performances entail a series of actions and circumstances that mean something. Or don’t mean anything.

It is, in other words, the moment that is very important. Other performance artists, like Meggy Rustamova, share that feeling. This does not stop her, however, from thinking when she sees someone’s taking a picture ‘Oh, I would like to have that as documentation’.

I don’t.

How do the pictures find their way back to you?

Usually by people I know and say they’ll send me the pictures or burn them on a disc.

The pictures only come to you from the outside world?

Yes, well, Anne-Mie also often takes pictures, but I don’t ask her to. She says herself that she prefers watching the performances as a spectator, because it is a different kind of experience.

But, on the other hand, for instance, I once did a performance in the cafeteria of M hka (8). Not really in M hka, because they never invite me to perform, but on the occasion of the presentation of a magazine for which I had made a contribution. Someone of M hka took photographs and filmed the performances, but I have never seen the pictures nor the recordings. M hka does not reason ‘We’ll give the artist a copy of those registrations’ because the M hka just wants to own, it does not want to give.

Other artists do give. When I take photographs of Meggy’s work when she performs at the Academy, then I will place them on a website immediately or I will burn her a CD, that’s how it is between artists and art lovers, but not with institutions.

Is there a noticeable tension between artist and the institutions and their care for their archive and collection?

They asked if they could film the performance and I said yes, but that is all. They cannot do anything with the images and, if they would do so without my consent, they’d have a problem. I am very difficult and fastidious about those kinds of things. If a video of mine is shown, I don’t have many, but if one of them is shown, a fee is to be paid. I have done about 160 performances and I think I might have video recordings of six of them. Some of them only lasting two minutes. But you can buy a DVD through the Club Moral web shop (9) for fifteen euros. Institutions don’t do that. And, by the way, it’s not because you have bought the DVD that you can screen it publicly, it is, at most, part of the collection. Films you buy at the Fnac cannot be shown publicly or exploited either. Publishing pictures of me without consent, that is not allowed. You mustn’t forget that I do not own anything else than my performance in itself and its documentation. You’re hardly paid anything to do the performance, it makes no sense that the documentation of the work would be free. That’s no different from the work of other artists, of painters and sculptors.

There wasn’t any reaction from M HKA towards you after the registration? Is it the same with other institutions, that the communication stalls in that respect?

Usually – at least in Belgium– that’s the case, yes.

Do you feel there is not sufficient dialogue between the artist and the institution? Or not enough room for dialogue?

No, the institutions assume they work with ‘art’, not with ‘artists’. With a performance this is of course especially difficult, but it is just the same with other art forms. When I see how Anne-Mie is sometimes asked to do a lot of things for nearly nothing, then I realise that any workman is better paid for any reparation of the sanitary conveniences in the institutions than the artists are for delivering an artistic work in the same institutions, while that is the institutions’ core business. When hiring a plumber the first question is always what it’ll cost, with an artist the first question is “Can you do this and that and that or can you make this for an exhibition?”, and when you ask about a fee, the answer is usually along the lines of “Oh, yes, we have a gift card for a book store or a volunteer’s fee for you”.

That is something to which I am radically opposed. I do not perform for free – definitely not for institutions. My price is set and is definitely not high when taking as a reference the common price for an artwork. Look at the prices of any artist who sells a drawing, you generally cannot buy it with the fee I ask for a performance. And I cannot earn anything of the work afterwards, I cannot exhibit it or sell it on. I do not commercialise my work either as I’m against that. But, anyway, that’s a different discussion.

In general, institutions appear to pay more attention to performance nowadays, in reaction to Marina Abramović and Tino Sehgal with his virtual contracts, but that seems to be very focused on the commercialisation of performance art. As a result, institutions seem to be looking primarily for a systematic way in which performances can be easily conserved and handled. How do you feel about this evolution?

I do not have any objection against that , but I do feel this should happen in full agreement with the artist and I prefer it not happening with people with the status of Abramović and people like her. I believe people such as Abramović are currently wrecking performance art for regular performance artists. It is an almost Machiavellian way of placing a select number of people on an altar and selling a video in five copies and thus to sanctify a number of things. I do not mind her [Abramović] doing that, but it shouldn’t become the norm. The problem is that Abramović, as she is currently profiling herself, has become an institute with a management and a commercial policy in order to realise several projects. At the same time, however, this closes the door for various other projects.

This counteracts the basics of performance art. Performance art has only been recognised as a true art form alongside sculpture and painting since the late 70s, together with land art, body art, conceptual art and, a little earlier, happenings and fluxus. Those form a cluster of art forms that was forcibly acknowledged as an art form by the contemporary pioneers of the 70s. They made sure it was recognised alongside the other traditional art forms. The institutions and art historians followed along in this acknowledgment. Somewhere in the 80s it appears to have died out, or halted at least. While artists have always continued to do performances. Then suddenly something strange happened, the circle of critics, historians, curators and institutions started saying “Yes, but we’ve already seen that”. I was told the same thing a couple of times when I was younger.

When I started doing performances, I had just turned 19, I didn’t have any art historical background, there was no Internet, there were no contemporary art museums in Belgium, there were no up-to-date libraries. It was difficult to get in touch with those things, with the performances that existed at that time. I have to say that other things that I have seen then, did influence me, but more in the sense that they confirmed what I was doing. Or they inspired me to further develop what was inside me and to present it more radically as artworks in themselves. It was a realisation that I could perform a whole array of vague actions as a legitimate form of art. Here, we are still talking about 1979. My origin is to be found in industrial culture, punk and new wave, in which I also did a number of physical actions, but I never realised that these were artworks as well. I did attend an art education (10), but I had never made the connection between what I did at home or at night under a bridge with the work I created at school. I never would have been able to make that connection without seeing other performances and happenings. That is what has made the connection between the two things for me: between my inner urge and where I wanted to go as an artist. Until then all you ever saw was, in my case, Pop Art and its derivatives, and that was the most advanced thing you could see as an 18-year old. Then, suddenly, there’s a reversal in the late 90s and there is no longer any interest coming from the institutions and art criticism because the pioneer aspect of ‘let’s experiment and see how far we might go’ has gone. Of course it has no use to have someone shoot through your arm again to find out what it is like, or if you do, it’s no longer an artwork, you wouldn’t claim it as a work of your own. This is in fact the same as people who paint, they continually see other things instead of painting yet another black square or a Campbell’s Soup can. The information is processed in your head and this results in you making your own work. On the other hand, I did not have the means to make videos at that time. If I would have had a video in five copies – I wouldn’t have had a clue as to what to do with them, because I knew nobody who would be interested, let alone who had the money to buy such an exclusive video. With that kind of videos you enter a different kind of realm that is primarily market oriented and which passes over the ephemerality of performance.

The numerous conferences and festivals on performance and its afterlife bear nevertheless witness to the fact that there is currently a revival of the interest in performance.

There might be more attention nowadays, but it is not of a serious nature. Unless in the form of Abramović who feels that the big icons should receive even more attention and that all others are merely derivatives of those icons. In other art disciplines there is still a broader view, with a kind of middle field, a differentiated interest, appreciation or, at the very least, mere attention for what the other artists are doing. When I see the amount of attention paid to performance in the visual arts press or in the regular press… that’s nothing.

And then there’s the strange way of approaching performance from within the field of visual art by the written press. You cannot bring those people to mind that they take away much of our potential to expand and of our recognition by not writing about us, and that the written press is often the only way in which we might make our work public. The painter has his paintings and pictures of his works, and those are more easily traded. A painter or a sculptor has a hundred times more opportunities to show his work, not once but a hundred times. It is difficult already to do a performance and often, when it is done, it is hushed up. And then those art journalists argue “Yes, well, we can’t write about them every time”. I don’t make a performance every two weeks. On top of it all, if the performance is written about, the coverage is often kind of strange. I did a performance in Singapore (11) as a result of certain circumstances, Anne-Mie participated in an official exhibition (12) and a lot of exponents of the Flemish press were flown out on the expenses of the Flemish Community to cover the exhibition. I went there on my own expenses because I knew some people there who wanted to organise a performance of mine. So I went there, I did my performance, and everybody was there, the museum director thought it was “the best thing I have seen”, the art journalist thought it was “unbelievable”, but did their statements yield me something?

Do you think this attitude is typical of Belgium?

I don’t know. I no longer have much contact with foreign artists. I used to have more. I think it is about the same everywhere, because when I see what other people are doing and how they spread the news about their activities, they are doing it in the same manner we are. We have created Club Moral as an association, because it imparts a slightly different aura to our work, in the sense that it is more than a freestanding event. But usually it is regarded as “Well, that’s easy, it’s your own association, you are promoting yourself ”. While, when no one else is doing it, you have to take matters into your own hands to make sure the world is aware of what your are doing.

Could this reside in a difference of objectives between the institutions and you, as an artist? In that they are aiming at commercialisation and you at a survival, a description of the performances?

I believe that – which is in fact pretty strange – it is the tangible, sellable and, as a result, market-valuable object that plays an important role. Another strange fact is that a museum occupies itself, in principle, with heritage rather than with the market value of art. I feel that it is the task of institutions – and that of the people who have studied art history and work there – not to go on about what has been around for numerous years, but to see what is done nowadays and how they will safeguard the art history of today. How they want to handle the heritage that is currently being made. The M hka is a museum of contemporary art and they don’t own anything made by us. I can make abstraction of the fact of whether it is my work, that of Meggy, that of Mikes, they don’t own anything. As a result a great deal of today’s heritage and of the heritage of the last thirty years is lost. Even though that is their function, they receive the means to do this, they are even assigned to do this by the Flemish Community. The grants they receive are to do this, not anything else. When I see what they show in their collection… You might say it is a matter of taste, but taste and heritage are, in my opinion, not exactly compatible, heritage should be above this. I know museums often use heritage as a kind of trump card, but when seeing the heritage that has been collected in the past thirty years, I wonder how people will look at it in 200 or 300 years. When at that time you want to see a cross-section of contemporary art in Belgium, a lot of works will be missing from those collections. In that view I feel that museums should have the guts to say right now that our work is not important enough, but they don’t. To tell other people that I’m a great artist is one thing, to do something with it, would be a whole lot better.

The fact that I do not commercialise my work is related to the fact that I want to make it accessible to everyone. As many people as possible should have the opportunity to easily see my work. The performances of which I have video recordings are burned onto DVDs and can be bought in the Club Moral web shop, for instance. And most of those things can be seen on YouTube as well. So if a museum would start by buying those DVDs, that would be a start. And if they then would be willing to show them in an exhibition, a fee might be discussed to show that exhibition for three months. Apart from this, there are hardly any costs, no construction, no transport, no insurance.

Yet the institutions take no initiative?

No. An example: in 2006 I started digging a hole, a work I named after Gordon Matta-Clark later on (13). Matta-Clark has realised his last major work Office Baroque here in Antwerp in 1977 and he died in 1978. It was an office building on the Ernest van Dijckkaai, right across from the Steen, in which he cut big notches by means of a circular saw, drills and bare hands. Those notches were made from the roof down to the basement. There was no museum for contemporary art back then and a number of artists, international artists, have tried to safeguard the work, partly under the influence of Flor Bex (14).

They tried to conserve Office Baroque and to turn it into a museum of contemporary art. All of those avant-garde artists have, subsequently, in the late 70s-80s donated works for the future museum. Matta-Clark died, the building was demolished and the works that were donated to save the building were more or less passed on to the collection of M HKA that opened its doors only in 1987. This was never the true intention of these artists, the donation of their work was a tribute to their colleague Matta-Clark. At M HKA, for a very long time, they did not do anything with those works, and apart from in the first exhibition they hardly ever exhibited work by Matta-Clark. I then started digging that hole and almost immediately I said I was referring to Gordon Matta-Clark’s work. I have been in the building in Antwerp at the time when I spend much time with Walter Van Rooy of Ruimte Z. The experience was very impressive, I believe Matta-Clark to be a great artist, because of his work and because of his social commitment. There are many different reasons why I named the work Diggin’ for Gordon. I started in 2006 and when you look at the exhibitions in and around the M hka, you suddenly see works by Matta-Clark appearing. But did M hka make the connection between me, digging that hole, and the work about Matta-Clark? That there was at least one reaction, for instance, referring to the webcam in the hole on their website or to place a photo of my work somewhere? In such a situation you really have to make a lot of effort to carry on. Alongside performances I also do a lot of things on the Internet because it is a medium very much alike a performance. You hardly need anything, you can make the work and it is immediately available to a great number of people. Or to send an email, to me that is a kind of artwork as well, not every email of course, but in just the same way as a letter, a stencil or a copy can be an artwork, an email can be an artwork. The art journalist says to this “We cannot be expected to write something about an email?”. Then I wonder whether he would have said the same thing to On Kawara in 1975, “We cannot be expected to write something about a post card you sent me?”. I find it very difficult to accept that people that are so closely connected with the world of art and know so much about art history talk such nonsense. Are they going to tell us what is art and what isn’t? We are still the artists.

The institutions are perhaps avoiding what they cannot mould into a tangible shape?

Yes, but in that case they should be looking for people who can; they should go along with their times.

All those people who graduate from universities as specialists in contemporary art history, are they going to continue writing about the 1970s, are they going to continue pretending as if the evolution of contemporary art stops there?

Should there be more attention from the institutional context?

Not just from the institutional context, but in general. The problem is that people always want to place performance in a different context, apart from other visual art forms. As I see it, I am nothing but a visual artist, the fact that I do different things does not change the core of that fact. Sometimes I create objects, often temporary objects, everything temporary. I do not believe in creating ‘the eternal object’ and selling it to someone a single time. I can accept that other people want to do that, but I don’t. It does not interest me. To me, that isn’t the essence of creating art. The fact that the ephemerality of art is generally regarded as a kind of eccentricity or as a reason to attach less importance to it, I have issues with that. I am just an artist, like any other artist whether he is a painter, sculptor or photographer. I do not do exactly the same thing, but in theory I do. The result is nothing else but an artwork. I do not mind that some people do not like my work, that they do not think it is interesting, or they don’t like the content or what else. But people who are professionally occupied with art, should acknowledge my work as a respectable form of art. I do not invent any discipline or art form, they have already been defined and recognised within art history, I do not have to demand a space for performance within contemporary art, it’s already there. I just want to receive the recognition that other forms of visual art receive and not just a kind of comparing recognition with the performance art of the 70s. Today, performance art is still being made. People still paint, and in that discipline it is not just Edward Hopper or Francis Bacon, abstract expressionism or Pop Art that serve as divine reference points. New developments are included and the things complement each other, and one thing is there because the other has been there. Strangely enough, I hardly ever read in texts about contemporary painting that they have ‘already seen that’, while everything has been painted at least a dozen of times by now, both in subject as in technique. As performers we have right to a place in the visual arts, alongside Chris Burden and Abramović, but also inbetween contemporary painting and sculpture and photography. It is a problem that they do not give us that place or that they do not allow us to have it, and the problem is with them, not with us.

Do you feel it might be useful to have a kind of platform where artists might engage in a dialogue about the afterlife of performance?

Recently I read there exists an interest group of performance artists. Firstly, it’s weird that I am not familiar with it. Secondly, how is it that those concerned have never contacted me? It’s not that I’m invisible. I no longer believe in consultation, by the way. Every once in a while there are some things , however; for example, the Momentum festival in Brussels. But there is something we haven’t touched this far, something that is really a thorn in my side: the attention the performing arts pay to performance. I really detest that. To them it suffices when on the (sometimes imaginary) stage one person hits another – be it rehearsed or not – to call it a performance and sell it thus. The performing arts thus spoil the market for performance artists.

Meggy finds herself on the boundaries of the two disciplines sometimes, probably to consider her livelihood. That’s her right, of course. I have different principles about this, but this implies that I currently work as a labourer to ensure my livelihood. But, for instance in the performing arts centres that profile themselves through performance, I’m sorry, but what is shown there is not performance. It’s what they call performance in America, a derivative of performing arts, the work of actors on stage and in films.

I have been to a conference in Paris, that centred on the influence of the avant-garde of the 70s on contemporary performance art (15). I was invited for an interview and an exposition about my work. In the expositions preceding mine, I was surprised to hear people from the theatre sector say that it was so progressive that they had erased the boundary, which was how they referred to the difference in height between stage and audience. That’s when I thought, ‘Well, this is not exactly what I am occupied with’. During my exposition there was one German in the audience who continued to ask very irritating questions in a kind of critical, teasing manner. He just kept on asking. Afterwards I learned that he was a famous theatre critic who thought that my exposition was a lecture performance, that I, as an actor, was playing a fictional character with fake YouTube-videos. That’s when you most strongly notice the difference in terminology, how what we call a performing artist is called a performer in America, and the performing arts gladly take on this habit. As soon as theatre is a little physical or when it includes nudity, they call it performance. Not in the least because in this way they might address a different kind of budget for their grants. The performing arts sector is very shrewd this way, in contrast to the visual arts sector, where performance artists are individual artists who work alone.

As an individual artist you’re not as adapt at compiling files and project proposals, it’s not something you’re primarily occupied with. By the way, how can I propose a project, when I don’t even know where I will end up at the moment they invite me. Usually, I can only say one week in advance what sort of performance it will be. Then I might say that they might want to provide a piece of plastic if they should care to keep the floor clean. But I cannot attach an allowance for expenses or a technical sheet to that.

According to you, what aspect of the performing arts’ attention for performance art spoils it the most? The tendency to work with scripts and files?

Yes, but also, when I pick up something or when I see what is happening in that field, I often find it all to be paper art. Made in function of that application file, that place, made to measure for the programme of that organisation or those available grants. That is the foundation on which it is decided where they might enact the performance. Everything is decided in advance, ‘we can offer this and for that we night this and that and, if necessary, we can perform it several times’. Whether it is twice the same product, this doesn’t matter, it’s a product; everything is finished the moment the application file is put together. Those artists experience nothing on the moment, when they are really creating their work. While, we, when we are doing a performance, experience something ourselves in that moment as well. Whether the spectators are touched by it or not, that’s not what primarily interests me. Suppose I cut my finger, what those people feel when I do that, it does not matter to me. It is difficult to explain, that’s an additional problem. When I cut my finger, it defines the further course of the performance. I more or less know what it is like when I cut my finger, but I’m never fully sure and whether, at that moment, five or twenty or people are watching, that will also play a role in the course of the performance. But this is the intrinsic value of the performance, that it is actually created in that moment.

When you have done it once, you know what it is like, you can never do it a second time, because it is all about the tension. It is in that moment you decide ‘Will I cut my finger there or there, or shall I just pop the knife into the table? Because the spectators already expect me to cut my finger’. That kind of intensity cannot be found in the performing arts centres and consorts. I have no use for repeating performances identically and I cannot repeat something this intense. When you are sitting face to face and I have a knife, there’s a tension, for me as well, because you are looking at each other, you’re thinking, what is important… they day after, I cannot do it like that, you can of course fake it… I might be able to do a series of performances, seven days, in which three people are allowed in each day. But I would do something different every day, seven times. The third time might include some aspects of the first day, but I won’t perform the same thing seven times. That’s why you cannot enter a kind of system in which you have to say three months in advance what they have to put in their programme.

It is impossible to work in that kind of system, because they will continually be asking “can you do this, can you deliver us a picture of the work and a description”. Well, that’s not possible.

It is, in other words, important that there are clear boundaries between performance art and the performing arts? That the use of the terminology changes?

Yes, I find clear boundaries very important. Institutions continually tell artists that they, the institutions, provide an environment in which art is properly placed. Consequently, we expect them to place performance art as well. Of course, there might be found a clear delineation between, for instance, sculpting and design, in which the institutions outline and defend the real art. But I have no knowledge of an institution that takes the stand for performance art, except for the theatres that increasingly pick up performances and claim them. While performance art belongs with visual art, the visual art institutions sometimes would rather be rid of performance. Soon the performing arts will have a patent on performance and I will no longer be able to say I am a performance artist because I don’t fit into their joint committee, as a matter of speaking.

All those half-hearted theatre performance festivals claim to explore the boundaries between the performing arts and visual arts, but they never really do it, there can never be found performances by visual artists at those festivals, or they force young artists to do something that is right up their street. As an artist you’re forced into a bodice while in fact it is unseemly of an institution to tell an artist what he should and should not do. I cannot imagine a museum inviting a painter for an exhibition and ask him not to use bright colours and to paint something he can easily paint again afterwards.

Do you think the problem is connected to the fact that the performances at those festivals often have to take place in a theatre, the so-called black box?

No. I did a performance in a theatre before. I worked with a professional boxer in a small theatre in Utrecht (16). I stood on the stage and on the other side of the stage The Simpletones (17) were playing. I just stood there and the boxer had to hit me. It was a very traditional theatre, with curtains and the audience was asked to stand up. It was all very exciting. I stood on the stage, The Simpletones were playing, the boxer came on, oiled up and in full regalia with gloves and jumping around me. In advance we had made an agreement, the first five minutes there would be nothing on stage but me, then five minutes with the boxer, then five minutes with just me standing there dazedly. In theory, of course, because you never know in advance how it will actually play out. But that was the plan, five minutes, five minutes, five minutes. That boxer was a true professional, when he hit me, he could estimate perfectly how hard the impact would be. The spectators soon realised he was not hitting at his hardest, but just as soon they realised they had to be very quiet and alert, for if the boxer would lose his concentration for just one second, I was done for. I sensed that as well. He hit me, I fell back a couple of steps, but it was not fake, he did hit me, just not too hard. It was not the intention to knock me out. It is still a very thrilling and intense moment to think back to, you cannot do something like that twice.

So, the theatre context does not necessarily make a difference. Next year I will make a kind of presentation in a theatre for a project in Amsterdam, based on my experience in Paris. In a building in Amsterdam, where people work during the day, I will change things at night. I’ll start with simple things, painting plinths, lower a door, then make a door open in the other direction, move a wall a little, construct a cube in a space that cannot get back out through the door… just to see what will happen. The project is called War Zone Amsterdam and engages artists from war zones and artists whose work focuses on war and terrorism. In different places I will also place cameras and buzzers. The whole thing will last about six months and continually evolve. Afterwards I will supposedly present a theatre piece at a theatre festival, a piece about privacy or something like that. All employees and users of the building will be invited to the theatre performance as a kind of company event and then I will just sit behind a table and explain what I have done, and show the images of the project.

I might also set up a couple of fake profiles on Facebook and friend people to find out what goes on in the building and how people react to my interventions. I have also asked a number of colleague performance artists to engage with the people of the building in the hallways and stuff like that. That ‘theatre performance’ will be my revenge at the performing arts. It will be a one-time event of course, and it will not be theatre, but just a couple of months of hard reality condensed to an hour. That’s my plan of resistance (18).

The use of performance in the world of theatre is actually nothing but a fad, and it will most likely pass eventually, but in the meantime they take away chances from us. It is too bad that we do not get any support from our sector. We fall by the wayside twice, both in the performing arts and in visual arts. As Social Commissioner and as president of the NICC (19), I have worked intensely on the status of the artist in Belgium. I have collaborated on breaking down the walls between the disciplines when realising the Decree of Arts. Nevertheless, I see how in visual arts and in literature the artist is tread upon. That is why I quit working for NICC. On the one hand, I quit because I believed the work to be done, but, on the other hand, because I was continually regarded as the rod between the wheels of the government and the institutions. After seven years I had had my fill. Later on my commitment shrivelled even further because I saw that deliberation and a kind of non-violent way of resistance did not work. I have worked hard (and mostly unpaid) on the Artist’s Status and the Arts Decree, and I am convinced that I might have realised a properly delineated context in which the artists would be able to do their work. But after the realisation of the Status and the Decree, the institutions simply wipe their feet on them and this meant war to me. That’s why I founded the Bastard Art Gruppe (20), inspired by the city guerrilla of the Rote Armee Fraktion in West-Germany and the Black Panthers in America.

So, despite the many conferences on aftercare with performance and the heightened interest in the art form, little has changed within the sector in the last couple of years?

Yes, it now has become a kind of circuit. In the 80s you also had a kind of circuit of festivals, but organised by the artists and performance-loving critics. Back then, there was a kind of network and you could regularly perform internationally because news and contacts were continually exchanged.

This kind of died out because of lack of interest and, of course, because of lack of means. We have also organised a lot through Club Moral (21), but then the institutions started up and they were funded by the government. We consciously never applied for grants to safeguard our individuality and independence. But gradually the art centres and the organisations for visual art have taken over that role. So now a new circuit is developing, but it is a closed one. The people who organise Momentum attend semi-theatre organisations as performance artists to do their performance. I participated in Momentum in 2009, but I sort of have the feeling that they primarily want to use the festival as a means to spread their own work and that they are using their contacts with a double agenda, and mostly for themselves and not for the artists they invite. I regret that.

NOTES

1. www.clubmoral.com/ddv/

2. Galerij Annie Gentils, Antwerp.

3. On March 27, 2008, the Antwerp artist Mikes Poppe re-enacted Danny Devos’ Thriller (1979).

4. Club Moral RVSTD, Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Antwerp, November 25, 2010. Performances by Nel Bonte, Meggy Rustamova, Mikes Poppe, Johanna Van Overmeir and Sébastien Rien with noussommesquatrevingt.

5. The Murder of Ilona Harke, Feldbachtal, Remscheid, Germany, 1993.

6. The Torture of Saint Erasmus, Chapel of the Roman Gate, Leuven, August 27, 1995.

7. A Chance Meeting of Yves Klein and Gordon Matta-Clark on the Gold Plated Corpse of James Lee Byars, Momentum Festival @ Bains::Connective, Brussels, June 6, 2009.

8. Aktion im ReforMuhka, A4 #2 Launch @ M hka, Antwerp, April 10, 2008.

9. www.clubmoral.com/talparaqual

10. At the Secondary Art Institution Sint-Lukas, Schaarbeek, Brussels.

11. James lee Byars was never in Art Ghraib and And Did Those Eyes in Recent Times, R.I.T.E.S. @ Old School, Singapore, August 12, 2009.

12. A Story of the Image, The Singapore Institute of Contemporary Arts, Singapore, August 14 till October 31, 2009.

13. Diggin’ for Gordon. From February 20, 2006 till 2010. The exact location of the work is unknown, spectators could watch the digging at all times via a live webcam feed.

14. Flor Bex was director of the ICC in Antwerp and had invited Gordon Matta-Clark to realise his Office Baroque there.

15. L’impact de l’Avant-garde Américaine en Europe et la Question de la Performance, Théàtre de la Colline, Paris, January 21-23, 2008.

16. This Week I was Beaten Up – 2, Mixage Festival @ Schouwburg, Utrecht, The Netherlands, November 29, 1980.

17. A band consisting of Johan Desmet (guitar) and Rudy Cabie (organ) who play simple, somewhat funny rhythmical music.

18. The War Zone Amsterdam project was cancelled in October 2011. ‘With pain in my heart, head and stomach and after many sleepless nights, I have decided yesterday to stop with War Zone Amsterdam. We received another rejection of a large application last week, and the gap between realization and finances is too big to bridge.’ Email by Brigitte van der Sande, October 4, 2011.

19. The NICC is an interest group of visual artists founded in 1998 after an occupation of the ICC in Antwerp

20. Various pamphlets, emails, flyers, posters and news about performances was spread under the name of Bastard Art Gruppe. More often than not they drew a bead on the art institutions and their policy towards artists.

21. Club Moral was one of the first so-called artists initiatives in Belgium where from 1980 until 1993 exhibitions, performances, gigs and lectures were organised. A large part of the activities was written about in the journal Force Mental (recently republished as a facsimile in one volume) that was published by Danny Devos and Anne-Mie van Kerckhoven from 1982 until 2005.

81